Respect for the Game

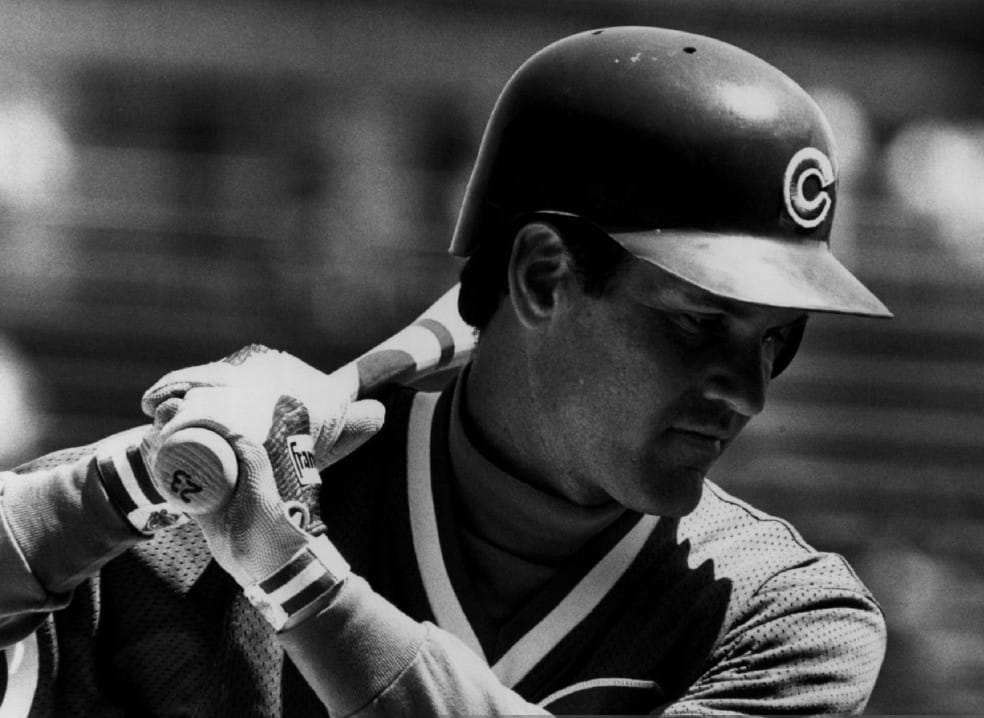

Ryne Sandberg understood that when a kid looks up at you with wide-eyed admiration, you don’t make a fool out of them. A tribute to the Cubs legend who respected the game, and us, too much to let us down.

Every generation that's played on an American sandlot carries a lighthouse name. A favorite ballplayer whose very mention can send a forgotten middle-aged man back in time and turn him into a kid again. Back to where he's chasing dusk‑lit grounders and his knees know no ache, where his swing is effortless and his back doesn't stay twisted for days after, and where the summers and the innings are infinite and he's yet to truly understand or appreciate that all games will one day end.

For many it was Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig, or Jimmie Foxx. To others it was Ted Williams, Joe DiMaggio, or Jackie Robinson, depending on which radio they fell asleep beside. To others it was Willie Mays, Hank Aaron, Tom Seaver, or Nolan Ryan. Our friends along the Mississippi and biggest rival rightly worship Stan Musial. South Siders of today may say Frank Thomas. Clemente, Koufax, Jackson, Morgan, Bench, Schmidt, Rose, Gibson, Banks, Stargell, McCovey, Ripken, Brett...listen, I can't list them all.

My Dad's was Mickey Mantle.

Mine's Ryne Sandberg.

Just seeing his name there that I typed just now, I'm back on a practice field and I'm mimicking his movement as best I can and I'm looking up at my Dad as he tosses a ball in the air and hits a hard one at me and I'm trying to play it just how Ryno would. I blink and I'm in a room with my friends in a basement or at the local pizza place after a game or I'm in our old family van on a summer road trip or I'm at the local pool and WGN is on the television or the radio and Harry Caray is being Harry Caray in the way that only Harry Caray was and I'm whispering the only prayer I know paired with the wish that Ryno can get one more at-bat. I close my eyes and I can hear the leather pop and the cracks of batting practice as I'm walking up the stairs and out of the tunnel behind the visitor's dugout at Wrigley, because that's the diamond side he played, and I can almost feel the warmth on my skin as I remember being enveloped in that impossibly golden afternoon sun that seemed to make the uniforms glow and I can smell that first whiff of the grass and the dust and the peanuts and the cracker jack and the beer and the hot dogs and..."There he is!" I point. "Dad, look! There's Ryno!"

For Chicagoland kids of a certain age, we imagined countless copies of our own personal Wrigley Fields in alleyways, cul-de-sacs, schoolyard parks, and forest‑preserve clearings and it was in those places we imagined ourselves as countless copies of him. Entire Little League teams from Hinsdale to Des Plaines to Libertyville to Naperville to Glen Ellyn and probably all the rest copied his stance as if city ordinances required it, but really it was because our volunteer coaches couldn't have asked for a better teacher on TV every afternoon. Hell, it may be true that every Midwestern kid of that time who ever dragged a glove through the dirt imagined themselves as the next Ryno.

I met him twice. The first was when he was doing promotional appearances for his memoir, Second to Home, co-written with Barry Rozner.

My Dad came rushing home from work one day and told me to grab all the baseball stuff I could find and get in the car.

"What...? Why?" I asked.

"We're gonna go meet him! We're gonna go meet RYNOOOOOOO!"

My younger siblings begged to come while I ran around the house and turned the garage upside down collecting pictures, posters, pennants, jerseys, baseball cards, magazines, gloves, balls, bats, notepads...anything. I waddled to the car with a literal pile of items tucked under my arms and stacked above my head. In a last‑second scramble, I sent my little 4-year-old brother back inside the house to go find his own souvenir, something he could "keep for himself."

On arrival I waddled in with all my stuff, only to be told by staff that he'd only be signing the new book. So Dad bought three copies and we went back to the parking lot to drop the items in the car. Dad winked and directed us to tuck some of the smaller items inside our jackets.

When it was our turn, I rushed forward and dumped the contents of my jacket and they spilled across the table. Ryno leaned back, a bit startled, and looked up at my dad who, with a shrug and a smirk that said, "kids, right(?!)" simply held up the three copies of the book he'd just bought.

That made Ryno laugh. He signed everything I could carry. I was beaming.

My little brother was last. He held out a baseball I had forced him to run back inside the house to get while we waited in the car. Ryno took it with a smile.

He bent to sign it and there was a pause. His face suddenly became serious. He looked up at my Dad. He looked down to me. To my sister. To my brother. And back to my Dad.

He spun the ball around.

To my horror, there on the baseball my little 4-year-old brother had run back into the house to grab for Ryne Sandberg to sign...was a White Sox logo.

We all had a good laugh. Dad told the story for years.

And yes, he signed it.

Many years later I had the chance to tell Sandberg that story and he jokingly insisted there was no way he signed that White Sox logo baseball...but he did. My not so little brother still has it.

For most of my life, Cubs fans forged its legends out of heartbreak. An entire industry was devoted to the scars. A 20th round draft pick out of Spokane, Washington, thrown into a 1982 trade with Philadelphia, wasn't supposed to become an MVP-Hall of Fame caliber folk hero but he made the leap. And this town, and Cubs fans everywhere, embraced him not just for what he could do but for how he did it.

Everyone this last week talked about The Sandberg Game and it's obviously his most iconic game and the game that made him a star, but I'll talk about a different one. April 22, 1990, at Wrigley Field.

It was the fifth inning. Luis Salazar picked up a routine bouncer at third and fired to second, where Sandberg met the ball at the bag the same way he always did to force-out the Pirate's Wally Backman. A simple play that was anything but ordinary. It was Sandberg’s 480th consecutive chance without an error, breaking Manny Trillo’s big-league record. He was 102 straight games deep into a defensive streak that would stretch to 123 error-free games and 584 clean chances, an MLB mark that stood for the next two decades.

In a season when his 40 homers grabbed headlines, the greatest fielding second baseman of all-time tipped his cap and got ready for the next pitch.

I don't need to reiterate the top line awards to you (ten consecutive All-Star appearances, nine Gold Gloves, seven Silver Sluggers, 1984 NL MVP, a league-leading forty home runs in 1990, a Hall of Fame plaque in 2005), or deep dive into the more impressive lesser known stats. I want to talk about the silence that made him special.

While cable broadcasts and the business of sport grew louder around him and cameras chased personalities and soundbites, Ryno just showed up. Quiet. Consistent as a Midwestern please and thank you. He didn't break your heart with off-season drama and, even during his abrupt early retirement to deal with the divorce of his first marriage in the mid-90’s, he did all he could to keep the media focus off his personal life and away from his kids. I mean, outside of immediate family and friends, how many really knew how bad this latest recurrance of metastatic prostate cancer was and how sick he was before he passed last week?

During his prime, the city would witness the rise of a sports hero on the basketball court that was larger than life, larger than the game he played itself, but Sandberg was life-sized. He made the spectacular look routine and never made the routine look like anything less than what it was: the foundation of everyday greatness. He was neither a cautionary tale nor a tragic figure. He just played, day after day, with a work ethic that mirrored the millions of fathers who did the same at their jobs and he respected the game too much to make it about himself. And that earned ours.

Long after the lights dimmed for him at Wrigley, Sandberg and his wife Margaret poured their energy into Ryno Kid Care, a nonprofit “dedicated to enhancing the lives of children with serious medical conditions and their families, by providing supportive, compassionate and meaningful programming.” The group matched gravely ill kids with volunteer “big brothers,” delivered home-cooked meals, and even dispatched costumed clowns to break the hospital gloom. It never chased headlines; it simply met frightened families where they were and stayed until the smiles returned. The humility that marked his double-play pivot found another field there, one without box-scores but every bit as sacred.

That's what we're really chasing. Not just the glory, but the grace. Not just the talent, but the humility. In a world that seems so frantic and desperate for attention, there's something to reflect on the quiet excellence of a man who understood that sometimes the most profound thing you can do is just show up and do your job. Sure, it helps if you’re one of the best to ever do it…

It's silly, I know. A grown man, reminiscing like this. Baseball's a game. Games are supposed to be fun. All that's really necessary is a stick, a ball, and a place to play. Yet the sandlot is practice for the bigger game we're playing. Every pitch asks you to either meet your opponent with courage or be ready for anything that comes your way, have faith in your team and yourself, and maybe hope for a lucky bounce. It's silly, I know. Nothing too important...not many parallels...

Growing older we learn grown‑up stuff. The game starts to feel small. A quaint diversion that merely occupies the corner TVs in bars where nobody listens to the sound anymore and would rather endlessly scroll their phones and share a meme with God knows who halfway across the world than share a moment with the person on the barstool next to them. We learn that knowing profit and loss statements and how we match up against our competitor's features are more important than knowing the win and loss percentage and starting pitcher splits against lefties, that the rise and fall of the futures markets are more important than the rise and fall of batting averages, and that the extra cold calls and late nights preparing presentations for early morning meetings to do deals and reach quota in the dog days of summer is more important to our end of year review with the department head who has to report to private equity board, none of whom give a damn about who got better at the trade deadline and only care what they can trade the damned company you work for in the next 18 months. The game’s patient rhythm that once reminded our hurried nation that revelation can wait, that suspense can simmer, and that the American story is told one pitch at a time, one day at a time, and always saves room for another inning as long as you're willing to fight for it fades just as the daylight turns to dusk on a long, lazy summer evening playing home run derby with your friends.

Yet moments arrive that pull us backward through the years, faster than any highlight reel, and we remember ourselves when we were little. And few things are as American or as seminal as Little League. When a kneel in the dirt was more important than a kneel at the altar, box scores were catechism, and baseball cards were holy relics.[1] And when one of our hometown childhood heroes walks into the field of dreams, the game is luminous again. He is luminous again. We are luminous again.

My favorite player as a kid is now gone.

Mostly, when these things happen, we're reminded of time. A time. Our time. The time.

My real hero was my dad, of course, and he never acted like Mickey Mantle was a saint and I would never presume Sandberg was. But so much of what we scroll through feels disposable. It's a world that seems determined to show us the worst in people, everywhere we look, and fewer and fewer seem to care about how they carry themselves. And worse, they don't care we know they don't care and they're happy to proclaim they don't care.

I never knew him. Not really. I mean, I know he had thoughts about books and movies and religion and politics and a thousand other things that had nothing to do with turning two or hitting the gap. Baseball was his job, his craft, and I’m sure it wasn’t everything he was. Still, for those of us watching from the bleachers and the couch cushions and the barstools of Chicagoland and elsewhere, he became something larger than himself, whether he wanted to or not. And I haven't heard a bad word about him.

Sandberg understood something that seems all but myth now. That when a kid looks up at you with that kind of wide-eyed admiration, you have a responsibility not to make a fool out of them. Not to embarrass the trust they’ve placed in you, even if you never asked for it. He carried himself like he knew we were watching, like he understood that somewhere a father and son may be talking about him on a car ride home. The memory holds not because of the statistics or the awards or the plaques or the statues, it holds because of that respect for us. For the kids. For the game. For the moment.

Our moment here, together.

Seasons end. Careers do, too. Childhood heroes age and pass away. But somewhere in time, there’s still a kid pointing from the stands, saying “There he is!” And somewhere in time, there’s a forgotten middle-aged man grateful that his baseball hero understood that when he invested his childhood wonder in him, it meant something. And for never making him regret it.

Good game, Ryno.

The Chicago Journal needs your support.

At just $12/year, your subscription not only helps us grow, it helps maintain our commitment to independent publishing.

If you're already a subscriber and you'd like to send a tip to continue to support the Chicago Journal, which we would greatly appreciate, you can do so at the following link:

Send a tip to the Chicago Journal

Notes & References

I still have three copies of Sandberg's 1983 Topps, by the way. ↩︎